LED Online Seminar 2018 - Working Group 5

--> Back to working group overview

Dear working group members. This is your group page and you will be completing the template gradually as we move through the seminar. Good luck and enjoy your collaboration!

Assignment 1 - Reading and Synthesizing Core Terminology

- You can read more details about this assignment here

- Readings are accessible via the resources page

Step 1: Your Landscape Democracy Manifestoes

Step 2: Define your readings

- Please add your readings selection for the terminology exercise before April 18:

A: Landscape and Democracy

Lynch, Kevin. (1960): The Image of the City, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press

Sieverts, Thomas (2003): Cities without cities. An interpretation of the Zwischenstadt. English language ed. London: Spon Press.

B: Concepts of Participation

Davis, Mike (1990): Fortress Los Angeles: The Militarization of Urban Space, From: City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles

David, Harvey (2003): The Right to the City, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Volume 27, Issue 4, pages 939–941

C: Community and Identity

Woodend, Lorayne (2013): A Study into the Practice of Machizukuri, RTPI

URBACT programme, The European Territorial Cooperation programme aiming to foster sustainable integrated urban development across Europe

D: Designing

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2013): Places in the Making: How Placemaking Builds Places and Communities

Wates, Nick: The Community Planning Handbook: How people can shape their cities, towns & villages in any part of the world (2nd ed 2014, Routledge)

E: Communicating a Vision

Potteiger, Matthew, and Jamie Purinton. 1998. Landscape narratives: design practices for telling stories. New York: J. Wiley. GoogleBook

Lejano, Raul P., Mrill Ingram, and Helen M. Ingram. 2013. The power of narrative in environmental networks. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Steps 3 and 4: Concepts Selection and definition

- Each group member selects three relevant concepts derived from his/her readings and synthesize them/publish them on the wiki by May 9, 2018

- Group members reflect within their groups and define their chosen concepts into a shared definition to be posted on the wiki by June 6, 2018.

- Other group members will be able to comment on the definitions until June 12, 2018

- Each group will also report on their process to come to a set of shared definitions of key landscape democracy concepts on the wiki documentation until June 20, 2018

Concepts and definitions

Author 1: Kazi Zayed Titumir

- (A:Community identity formation in pontchartrain park:Journal of Urban History 39:36,Gafford, Farrah D. (2013))

Communal bondings are the most important for neighbourhood The interrelation between community and neighborhood provide opportunities to individual and family to develop their skill and knowledge. And also it boosts the self esteem, responsibility, and belongingness toward the community.

- (B:Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Sustainable Happiness: Hester, Randolph)

Isolation from the world creates immense impact on our brain Disassociation with the world gives us the feeling of freedom. But, the impact for very short period. Whether, it has a tremendous long term impact on us. Separation from nature, environment and community gives us a negative effect on everything.

- (C: A Refrain with a View, UC Berkeley, Hester, Randolph (1999))

Participatory action equalizes power Participatory approach, mainly reduces the dependency on administrative people. It segregates all the workload and liabilities on stakeholder, so that, they can propose what exactly their demands are. It creates the balance.

Author 2: Mastaneh Mahfouzi

- ( A: Landscape and Democracy - Mapping the Terrain: Burckhardt, Lucius (1979): Why is landscape beautiful? in Fezer/Schmitz (Eds.) Rethinking Man-made Environments (2012))

Different perception of landscape landscape is a subjective reality, a certain landscape Scene can convey different meanings and feelings to different people due to their personality, culture,pre-expectation and etc. So different observers have different ideas about a certain place, in consequence, everyone has not the same charming place in mind.

- (B: Concepts of Participation: Day, Christopher (2002): Consensus Design, Architectural Press )

simultaneously cooperation of designers and owners Emotion demands are the invisible level of life, But also one of the most important and fundamental features in designing. in order to consider this feature of life, it's crucial that professionals and designers work simultaneously with users in order to reach subtle qualities and also provide all needs and demands of owners.

- (C:Designing: Hester, Randolph: Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Sustainable Happiness)

Satisfaction through sustainability: Sustainability can bring satisfaction for residents of a city in different aspects. A sustainable city should include three distinctive traits: enabling form, resilient form and impelling form. enabling form:We need new forms of habitation that let us feel, understand and empathize with the multiple roles in our ecosystems

Resilient form: In order to consider resiliently in a city at the scale of land use, They should be less dependent on nonrenewable energy sources.

Impelling Form: Impelling form should offer alternatives, be simple enough to comprehend

Author 3: Atiye Asadiha

- (Woodend, Lorayne (2013): A Study into the Practice of Machizukuri)

The importance of an understanding of the historic, cultural and recognizing and capitalizing upon the benefits and contributions of the multiple activities of communities towards the common aims of sustainability.

- (Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2013): Places in the Making: How Place-making Builds Places and Communities)

The best forms of community engagement, and in fact the best forms of place-making, are those that recognize and exploit the virtuous cycle of mutual stewardship between community and place.

- (Nassauer, Joan Iverson (1995): Culture and Changing Landscape Structure, Landscape Ecology, vol. 10 no. 4)

humans not only construct and manage landscapes, they also look at them, and they make decisions based upon what they see (and know, and feel). This dynamic helps to explain landscape structure as both an effect of culture and as an artifact that changes culture.

Author 4: ...

- ......

- .......

- .......

Author 5: Oleksandr Galychyn

- Imaginable landscapes are the path dependent single or multiple symbolic orderings (common assemblage networks) within specific community that pass to the the next generation as generalized knowledge through human or (non-human) mediator to foster a sense of community among the individuals.

- The debates the regarding the Right to the City open of question for the establishment of the new urban actor-civic society as a mediator in the participatory governance model to open a road towards an 'inclusive city'. An application of such actor to the urban planning process creates an opportunity for the realization of the spatially just society; therefore, the spatially just community is a community that both employs a participatory governance model at the local level and surpasses formal/informal functional restrictions towards the mutual partnership of during the neighborhoods lifecycle

- The 町造り(Machizukuri) can be perceived as the process of 'space making' that involve the local (urban) participatory network of residents and non-profit organization (research institutes, universities) organized for the entire urban lifecycle in accordance with the principles of innovation, knowledge and learning . The community involvement in the fusion of planning and design placed in the center of aspect the central role since design absent in the USA communities. Japanese perceive the community design process as the management and maintenance of infrastructural networks between buildings and the urban space during the entire lifecycle to preserve their imaginable landscapes as a collective identity for the future generations.

Step 5: Reflection

Isolation from the world creates an immense impact on our brain : Globalisation has disconnected the people from the immediate environment by virtual connection to the local community instead of direct interaction. The virtual interaction contributes to the lower levels of public participation due to the lack of knowledge regarding the details of the context and the lack of computer literacy (kids and aged population), a negative network effect (over-enrolment of users into the network) and health problems associated with this type of activity. Particularly, the isolation occurs in the urban slums and abusive environment where fear of the ‘outside crime’ and an interaction with a poor occurs. The lack of literacy as well as health and mental and maintenance problems became a common occurrence at the long-term perspective. The feeling of safety with the time changes into more profound fear resulting in the barricades and complex security system (gates and fences, security guards, CCTV). The residents without knowledge of the community became as an ‘outsiders’- non-actors that lack qualifications to engage in the planning and design of their community. In other words, the top-down planning and profit maximization prevail while residents being ripped from their benefits (physical, financial esthetical, etc.). Moreover, they lose their status as mediators for future generations; therefore, the poorer sense of community contribute and out-migration and at the long-term perspective the overall decline and with a potential to became an attraction pole of squatters. The social exclusion is the major obstacle to the well-being of the community.

Landscape Knowledge: The continual interactive participation process involves decisions based on local knowledge and experience that shaped before design and planning phase of community building as a means to adapt the community design to the pre-existing social networks, cultural heritage, and local resources and constantly employed by residents in their feedback to community designers. This dynamic processes allows to explain fragmentation of the social network as a result of intrinsic socio-economical and cultural boundaries ( as perceived by residents) within the community landscape and changes this pattern brings to the access and mobilization of community resources, natural and anthropogenic (artefacts) such as facilities and services, thereby making changes in the multi-cultural organization.

Different perception of landscape: While the special landscape knowledge is generalized (common wisdom) to be passed through storytelling by human or non-human mediators to pass to the next generation as a local knowledge to raise awareness regarding the community issues and the local resources (natural and artificial) that community to be able to combat those issues. This generalized knowledge (comprehensive narrative) is shaped from the individual stories for visualization of a whole picture or a detached artifact (fragmented images)- a product (output) of an individual perception. Each community can have multi-cultural organization, each family has each own value, and the nature of relationships and the roles of members within the the same cultural group as well as family, socio-economical group or in generalized sense environment where the person has been born and formed multiple identities are the factors that change the individual perception of a landscape and a the choice of environment to connect, disconnect and re-connect within the social network of the community. For instance, the connection can be virtual and direct depending on the fact if the individual is a foreigner separated from the land of his ancestors or the part of the same community over the course of life. Therefore, before the design and planning a new community of before the renewal of the existing ones its essential to build an inclusive community in the social sense to make a decision on the basis of the complete assemblage of the individual stories that allow to account for the drawback and opportunities in the networked pattern of the neighborhood.

Imaginable landscapes: Imaginable landscapes are historical patterns of trails that ancestors have used to satisfy their common needs (manly sacred, military or food purposes). From the initial abstract ‘diagrams’ of trails and river bands (nature) without any landmarks (artefacts) overlapped with the cosmographical objects (birds, star crosses etc.) invoked by the individuals through memory and dream (mnemonic function) and trance (ceremonial function) to the postcolonial ‘mind maps’ of the common landscape reachable by foot of culturally bounded symbolic landmarks. The later generations have received this generalized knowledge for their survival (for example to find water source by following mountain trails), protection and appreciation of nature (star crosses) and gods as well as the referent points (navigation). Those networks of symbolic images engraved in individual minds (mediator) to pass on the future generations directly or by means of rock art (mediator), namely carvings, paintings or drawings, some of which incorporated not only the celestial realm but also a spatial arrangement. Other mediators can be too fragile to transmit special knowledge. For example, bark, wood or skin wasn’t able to preserve any images. Since the different cultures can inhabit the same land without any linkage to the pre-existing cultures, often the contents are mixed without any comprehensive (generalized) graphical information. The community is more complex than a cultural region since this unit incorporates geographical barriers, the relationship to other cultural regions in terms of a hierarchy of influences as well as artifacts (physical objects). The patterns must be dated back to their origins in relation to the geographical and cultural contexts in which they have carved or painted. Thus, the proper cartographical and cosmographical interpretation is achievable only if the current community members have the deep linkage with their ancestors.

Landscape Project various features: Landscape has different features and different aspects which contain various issues. in a landscape project different people are involved and in order to have a successful project, we should consider all subjects such as historical background and social, Economical, environmental issues. we should be aware of all stakeholders and how they behave. Also, we should consider that landscape is a subjective reality. the landscape is affected by culture and also it can affect culture .so it is difficult to reach a high quality and provide all demands.

Step 6: Revised manifestoes

- please look again at your initial manifestoes and update them with any new aspects/prespectives you have taken up during this seminar

Assignment 2 - Your Landscape Symbols

- You can read more details about this assignment here

Landscape Symbols Author 1: ...

- Symbol yourname photovoice3

add a caption (one paragraph max) description of the symbolism, interpretation, as well as geo-location

Landscape Symbols Author 2: ...

The "Azadi Tower" is a monument located in Tehran-Iran. It is one of the landmarks of Tehran, marking the west entrance to the city. Today, the tower is somehow the Symbol of Tehran and its picture is seen in Every card postal of TehranAlthough It was commissioned by the last Shah of Iran, before the revolutionary, today it has still the same meaning for people and even young people who were born after the revolution has the same feeling about it.

The "Naghshe Jahan" is a historical public place in Esfahan-Iran. Around Naghshe Jahan there are plenty of different functions such as Mosque, Bazar, Chovgan playground(an old sport), palace, restaurants, cafes and... which attract a lot of people for pleasure, pray, shopping and other activities. The meaning and function of this square have not changed a lot During the time and it is still one of the important trade and also pleasure spots in Esfahan.

Landscape Symbols Auther 3: ...

Landscape Symbols Author 4: ...

- Symbol yourname photovoice1

add a caption (one paragraph max) description of the symbolism, interpretation, as well as geo-location

- Symbol yourname photovoice2

add a caption (one paragraph max) description of the symbolism, interpretation, as well as geo-location

- Symbol yourname photovoice3

add a caption (one paragraph max) description of the symbolism, interpretation, as well as geo-location

Landscape Symbols Author 5: ...

MSFAU was initially founded as the archeological museum to retain archeological finds of national enterprises in Ottoman Empire. At present this building is a symbol of equality for all in terms of art and architecture education (social) as well as the nostalgia that takes back to the Ottoman times palaces (historical), and rises a sense of national identity among the visitors of Istanbul (political).

The significance of Basilica Cistern, a one of symbols of Istanbul, at present reaches even a supranational scale. Currently, the local population views it as a symbol of technological dominance and centralized power (owing water means owing the gold) of ‘their own past’ (historical), protection from evil spirits (religious) and unequal access to the resources (social).To me it means ‘ the passage between our world and the underworld (realm of Hades)’.

The Dolmabahçe Palace was initially ( in 1856) planned as mixed-use multi-purpose complex that served as a means of separation of Sultan from its own nation. The ‘Dolmabahçe’ literally means ‘the filled garden’. This phrase can be understood as a mixed-use development, one of principles of sustainable community. Other cultures can understood this phrase as ‘gated community in old fashion’ or just view this palace as a simple museum without any complex symbolic definition.

Assignment 3 - Role Play on Landscape Democracy "movers and shakers"

- You can read more details about this assignment here

Oleksandr Galychyn: Prof. Marc Francis (how public participation in planning and design triggered durable social networks in Village Homes in Davis)

Assignment 4 - Your Landscape Democracy Challenge

- You can read more details about this assignment here

- Each group member will specify a landscape democracy challenge in his/her environment

- Each Landscape Democracy Challenge should be linked to two or three of UN's 17 sustainable development Goals

Landscape Democracy Challenge 1

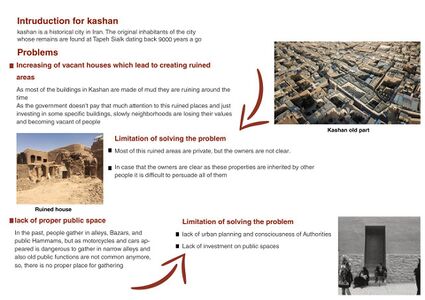

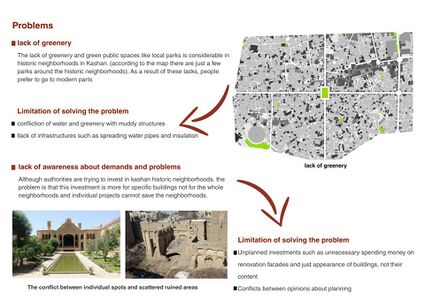

- Revival historic neighborhoods with Greenery

caption: Kashan is a historical city in Iran.The original inhabitants of the city, whose remains are found at Tapeh Sialk dating back 9,000 years. There are a lot of historical houses and other precious building in Kashan. As I know this city well and I have done some projects there, I think, Kashan is losing its values gradually, so it's crucial to find out the problems and work on them.

caption: As most of the buildings in Kashan are made of mud they are ruining during the time. But as some of them, don't have a specific owner or the owners don't have enough budget they are destroyed gradually. So there are plenty of ruined houses which have the potential to be alive again but instead, they are becoming the place of accumulating rubbish or a spot for addicts and ...

caption: In past people gather in alleys and in front of houses or in the bazaar and public hammams, but as motorcycles and cars appeared its dangerous to gather in narrow alleys and also old public places like bazar and Hammams are not common anymore, there is no place for gathering. On the other hand, The lack of greenery and green public spaces like local parks is considerable.(according to the map there are just a few parks around the historic neighborhoods). As a result of these lacks, people prefer to go to modern parts.

Your references:

- Alexander, Christopher,(1977), Pattern Language

- Habibi,Mohsen,(2015) Urban renovation

Landscape Democracy Challenge 2

- Regenerating aqua life in dense urban fabric

caption: This is Dhaka, which is the capital of Bangladesh. I choose this case because this city is right now facing tremendous amount of pressure from water pollution. Dhaka is one of the most highly dense cities in the world. Right now the population is above 19 million. Parallel of air pollution, water pollution is so acute in this city. Waterbodies, rivers are becoming unusable for it's industrial wastes, as well as toxic components from outside.

caption: Slum dwellers and low income people often live beside the river banks. They don't have proper sanitation system or waste disposal facility. So they throw all of their wastes directly in the river. They don't have proper knowledge of waste management, neither about the health of the river. They are not even aware about the effect of this actions on the environment.

Your references:

- ...

- ...

Landscape Democracy Challenge 3

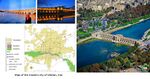

- Water crisis and Zayanderud dried river in Isfahan,Iran

Water crisis is one of the main concerns of Iran today . Because of the hot and dry climate of Iran, Water was the main factor to determine cities places and most of the cities are located near rivers and lakes. Unfortunately because of many reasons Iran is getting dry more and during the last decade caused to dry some of main points, like Zayande rud river in Isfahan.

Isfahan is one of the oldest and most beautiful cities of the world that every year has many visitors from all over the world. Zayande rood is a river which the city has built around it and actually the city is known by this river. It has also several historical bridges on it that became tragedy next to dried river …

This issue led to other problems such as :Economy: Agriculture and tourism are the main income way of people that this issue effect both of them, tourism rate has decreased about 19% . Social: according to the researches by university of Isfahan, It Increased rate of depression and anxiety also it has declined social communications. Ecosystem: this situation also had a terrible impact on ecosystem and caused aquatic mortality and birds migration.

Your references:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Water_crisis_in_Iran#Water_crisis

- https://www.mehrnews.com/news/2349058/%D8%B2%D8%A7%DB%8C%D9%86%D8%AF%D9%87-%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%AF-%DA%86%DA%AF%D9%88%D9%86%D9%87-%D8%AE%D8%B4%DA%A9-%D8%B4%D8%AF-%D9%88%D9%82%D8%AA%DB%8C-%D9%85%D8%AF%DB%8C%D8%B1%DB%8C%D8%AA-%DA%86%D9%86%D8%AF%DA%AF%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%87-%D8%B2%D8%A7%DB%8C%D9%86%D8%AF%D9%87-%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%AF-%D8%B1%D8%A7-%D8%AE%D8%B4%DA%A9

- http://www.visualcapitalist.com/extreme-water-shortages-are-expected-to-hit-these-countries-by-2040/

- https://www.mehrnews.com/news/2302137/%D8%AA%D8%A3%D8%AB%DB%8C%D8%B1-%D8%AE%D8%B4%DA%A9%DB%8C-%D8%B2%D8%A7%DB%8C%D9%86%D8%AF%D9%87-%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%AF-%D8%AF%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%81%D8%B3%D8%B1%D8%AF%DA%AF%DB%8C-%D9%85%D8%B1%D8%AF%D9%85-%D8%A7%D8%B5%D9%81%D9%87%D8%A7%D9%86-%D8%AE%D8%B4%DA%A9%D8%B3%D8%A7%D9%84%DB%8C-%D8%A2%D8%B3%DB%8C%D8%A8-%D8%A8%D8%B2%D8%B1%DA%AF%DB%8C

Landscape Democracy Challenge 4

- Give a title to your challenge

- Yourname challenge 1.jpg

caption: why did you select this case?

- Yourname challenge 2.jpg

caption: what is the issue/conflict (1)

- Yourname challenge 3.jpg

caption: what is the issue/conflict (2)

- Yourname challenge 4.jpg

caption: who are the actors?

- Yourname challenge 5.jpg

caption: UN's Sustainable Development Goal?

- Yourname challenge 6.jpg

caption: UN's Sustainable Development Goal?

Your references:

- ...

- ...

Landscape Democracy Challenge 5_OLEKSANDR GALYCHYN

- Social exclusion of Scampia neighborhood

The social stigma associated with the gated communities in Scampia, emerged due to the Scampia neighborhood became the reason of social and physical separation and render an image of the most dangerous neighborhood in European Union. This fact confirmed during the meeting with the major actors that reside in the district as well as marginal workers (residents of slums)a few months ago during the case study as part of Erasmus+ project.

The illegal occupation of the incomplete and recently complete lots ( especially, M and L with the ‘Velle della Scampia’ ) after the earthquake by the homeless. Seven sails of M and L lots have been transformed into the squatter houses at the beginning of 80s, where landlords have pursued profits from unregistered homeless tenants.

The seven Sails of the architect Di Salvo represents a visual perfection without the physical(pedestrian-oriented design, resident-oriented facilities, traffic calming measures, etc.) and social integration (housing design) in the surrounding context. The underground space exists in four remained Sails (lot M)basements occupied by squatters " scantintisti".

The private sector is absent. The provincial administration is responsible for the planning and design while numerous NGO, formal and informal organization (bottom-up) are the main actors in everyday management and maintenance (territory outside of urban slums and gated communities). Any of the proposed local redevelopment plans in collaboration with the Neapolitan architects and university professors were never implemented. In addition, strong bottom-up participatory activities of the lower-middle class are separated physically by means of a public facility (park)result in the support been "virtual" through indirect action rather than "actual" through the direct involvement(concerts at the main square in the park).

- Poverty manifests itself in the everyday life of the lower income class (squatters and temporary laborers called i drop out), lower middle class except workers of public services. Poverty is one of the main reasons allowing drug business circulate among the school kids and the adults capturing lifestyle communities and urban slums in the danger. By this criteria 'Scampia" not only outnumber the neighborhoods in other EU countries but even the Turkish provinces with unbalanced regional development.

The reduction of inequality in Scampia is directly related to poverty since the disparities in access to education, health and work opportunities are evident among the social classes and the nationalities.The fear creates a gated nature of the neighborhood where the only lower middle class (workers of public services and families with many children) utilize the facilities and services in their respective territory. The right of access to all must be archived to prevent out-migration and subsequent decline of the neighborhood (ghost neighborhood).

Your references:

- Public policies for Scampia neighborhood in Naples, NEHOM ( Neighborhood Housing Models), 2003.

- Gizzi S. Problems of Sails, published in Castagnaro A. , Lavaggi A. Proceedings of Conference: What to do with

Sails of Scampia? Giannini; 2011. p.31-34

Assignment 5 - Your Democratic Change Process

- You can read more details about this assignment here

- After documenting and reflecting on your challenges you will continue jointly with one of these challenges and design a democratic change process

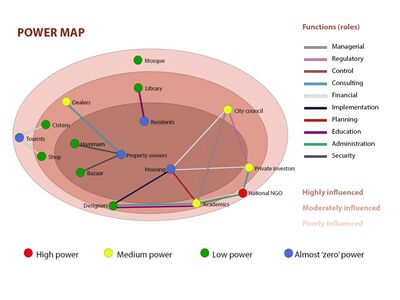

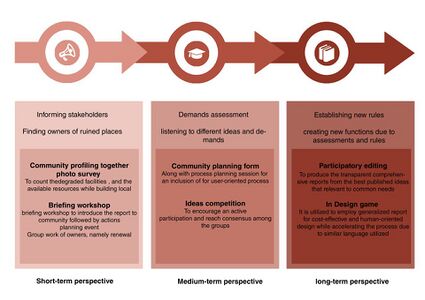

Your Democratic Change Process

- Add Title

Reflection

- Decision making should be transparent to everyone.

- The investment of resources should be well distributed.

- Public participation enhances the possibility of democratic decision.

- Historical studies of the project is the responsibility of both designers and community. It should be done by residents before the initiation of any change process.

- Community profiling and photo survey may be very useful for identifying internal factors (stretches and weaknesses) if are based on local knowledge

Conclusion:

- The financial stakeholder creates the major role.

- The problem will be unsolved if the tenancy is not secured.

- We need to establish new policies supporting public participation.

- The SWOT analysis can be more fitting to the real context if the understanding of the community and data collection involves a combination of methods correspond to the historical limitations and local

- The community linkage to the pre-existent cultures influence hierarchy decision-making process towards Bottom-Up design

Your references

- Habibi, M.,& Maghsoudi, M. (2009). Urban Renovation. Tehran: University of Tehran Press

- Falamaki, M.(2015). Reviving the buildings and historical cities. Tehran. University of Tehran Press.

- Habibi, M.(2011). DE LA CITE A LA VILLE.Tehran. Tehran University