LED2LEAP 2022 - Budapest Team

>>>back to working groups overview

For help with editing this Wiki page use this link.

For more details on assignments and key readings please use this link.

Landscape Democracy Rationale

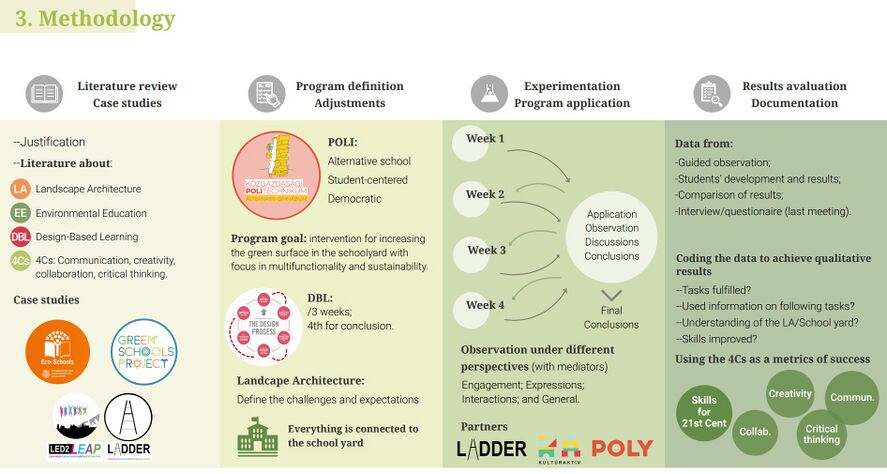

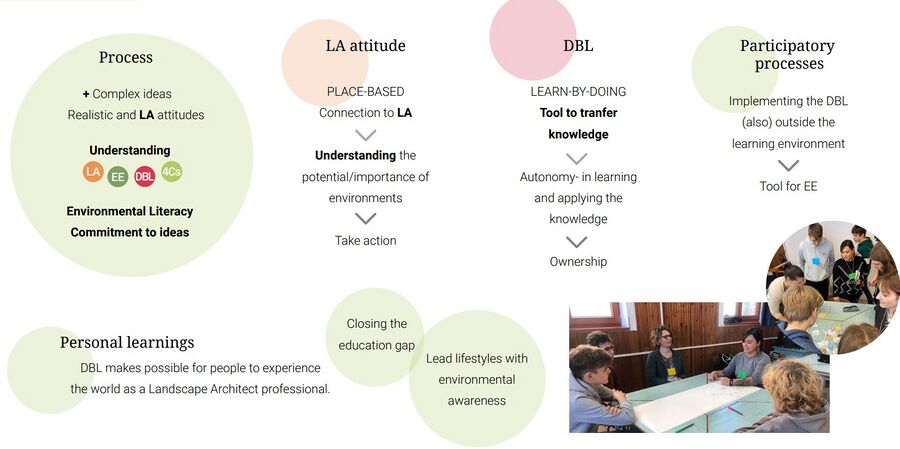

An effective tool for determining the future of the natural environment and its resources is the improvement of environmental education in schools. To achieve such, more connection between the students and the landscape in which they belong, in this case the schoolyard, is an important first step. To accomplish this aim the Design-based Learning (DBL) methodology, or learning-by-doing, and the set of skills associated with landscape architecture (LA) can be particularly helpful.

How can a program Designed for a specific community, applying concepts of DBL and LA, help in achieving a more involved student community towards their schoolyard?

Location and Scope

Polytechnic of Economics is an alternative bilingual high school, with pedagogical objectives related to alternative pedagogical movements, and continuously integrating modern pedagogical methodology into the daily teaching practice: cooperation, development of creativity, use of modern IT and communication tools, project work, extracurricular educational programs, and activities-based learning. It is also a person-centered school, meaning that the learner is at focus, having an integrative and personal character, offering opportunities to develop the students’ personalities.

Phase A: Mapping Your Community

Welcome to Your Community and Their Landscape

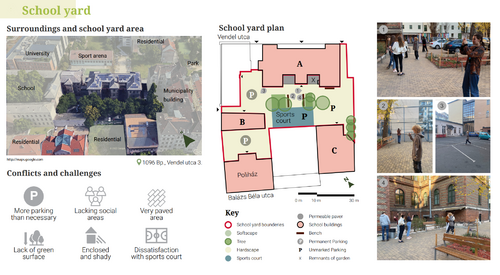

The building is in a very densely built area, being surrounded by a municipality building in the southeast, to which the car entrance and some parking take place inside the schoolyard, Semmelweis University is to the north of the school, to the west, polytechnic shares a wall with another school Leövey Klára Gimnázium, while the remaining borders are shared with residential buildings.

Within the school grounds, 4 different buildings are used for different functions, buildings A and Poliház are classrooms, building B is a woodwork and crafts workshop and building C is a PE center.

Within the schoolyard area, there are two assigned parking areas, but also, the area in front of building C and the sports court are used as parking. In the whole yard, there is a small area of soft scape surface, within which there are a few well-established tall trees, a few smaller and multibranched threes, and formal shrubs of about 1,5m tall.

Some smaller level plantations can be found in the few planters distributed around the yard, also present are the remnants of a rock garden, which is no longer being maintained. Due to its enclosed character, the yard is very shady and lacks social areas for the students, having some park benches distributed in the surroundings of building A, and play equipment and artistic displays are nowhere to be found.

In a visit to the school it was pointed out some of the dissatisfaction of the students and some of the changes being considered for the future of the yard by the school administration. Among the topics raised, there was the discussion about the sports court, which the students dislike the appearance, nicknaming it a cage; position, complaining it takes up a lot of open space of the yard; and the fact that it is also used as parking. When it comes to the parking, the administration itself agrees there are more parking areas than actually necessary, and there is a general agreement on the necessity to increase the green surface within the area.

Groups of Actors and Stakeholders in Your Community

Relationships Between Your Actors and Groups

Summary of Your Learnings from the Transnational Discussion Panel

Theory Reflection

Design-Based Learning

Design is a very open concept, it can be applied to many contexts when understood as a tool to put into practice one idea, using a process to solve a problem, or also as a means to achieve an aim. Under this perspective, we are constantly designing on a subconscious level. Consequently, design is a part of our daily lives.

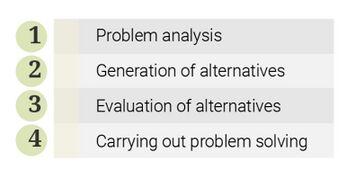

Löbach (2001) is one of the authors to show a simplified version of the design methodology to expand its applicability. The author divides the process into four phases, defining it as a method for the solution of a problem.

1. Problem analysis

2. Generation of alternatives

3. Evaluation of alternatives

4. Carrying out problem solving

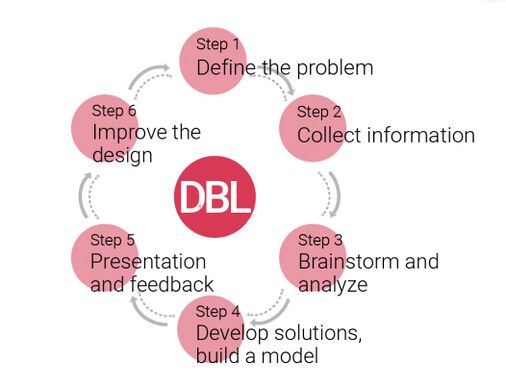

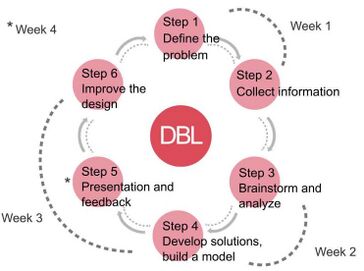

Among the many adaptations, one that summarizes well all the steps necessary while also being open to a variety of fields of knowledge is the self-explanatory 6 steps method (DISCOVER DESIGN, 2012)

1. Define the problem

2. Collect information

3. Brainstorm and analyze

4. Develop solutions, build a model

5. Presentation and feedback

6. Improve the design

Davis (1997, p. 3) maintains, “if society values the thinking and problem-solving behaviors exhibited by designers, there must be greater investment in developing these skills in all students across all subject areas. One way to accomplish this is to involve students directly in the design process”. Hence, another method based on the design that was also brought to light, the Design-Based Learning process (DBL), as described by Jiang et al (2020, p. 4) it is “an inquiry-based form of learning, or pedagogy, that is based on the integration of design thinking and the design process into the classroom in general as well as professional education”.

The DBL methodology is highly recommended for the needs of the youth of the 21st century as the students need to quickly improve their self-learning capabilities to be up to date with the fast and ever-changing circumstances, being them technological, global, economic, or social (BARRON, DARLING-HAMMOND, 2008). The method is student-centered and allows the pupils to discover how to learn while taking action, going beyond theory, and applying and testing discoveries and theories. Besides, developing a very valuable set of soft and hard skills.

Nature connection

As suggested by Van der Toorn (2007), another factor of success to be considered for the future of environmental education is “the creation of direct experiences in the environment of daily life” (p. 461). The author also implies that integrating this approach helps with the formation of sensitive, well-informed citizens with the capacity to connect their experiences on a global scale.

References

BARRON, Bridget; DARLING-HAMMOND, Linda. Powerful Learning: Studies Show Deep Understanding Derives from Collaborative Methods. Edutopia, 2008. Available at: https://www.edutopia.org/inquiry-project-learning-research. Accessed in: 20, Oct, 2021.

DAVIS, Meredith et al. Design as a catalyst for learning. Virginia, USA: Association for supervision and curriculum development, 1997.

DISCOVER DESIGN, 2012. Available at: <https://discoverdesign.org/handbook>. Accessed in 18, Oct, 2021

JIANG, Zhigang; et al. Teaching towards Design-Based Learning in Manufacturing Technology Course: Sino–Australia. Sustainability journal, MDPI, Switzerland. 2020. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340918107_Teaching_towards_Desig n-ased_Learning_in_Manufacturing_Technology_Course_Sino-Australia_Joint_Undergradu ate_Program>. Accessed in: 18, Feb, 2022.

LÖBACH, Bernd. Industrial Design: Bases for the configuration of industrial products. [original in Portuguese]. São Paulo, Brazil: Edgard Blucher Ltda. 1st ed. 2001.

VAN DER TOORN, Martin. Environmental education and design: the role of landscape architecture. WSEAS Int. Conf. on environment, ecosystems, and development. Edit. 5. p. 451- 462. 14-16, dec. 2007.

Phase B: Democratic Landscape Analysis and Assessment

LADDER game application

The school was already in partnership with the LADDER project and KultúrAktív NGO, which is associated with the Landscape and Democracy discipline of MATE, having some activities related to the course conducted with the school community in the previous semester. Volunteer students were called to test and analyze the results of a game developed by landscape architecture students from MATE. The idea of the game is to encourage the students to rethink their schoolyard, evoking ideas and thoughts that help them brainstorm. This is achieved through a role-playing type of game, in which the students are assigned different personas and are questioned about how would be the dream yard to the assigned character. The game is cooperative, not based on competition, in a way that the students have to work together and combine the desires and knowledge of their characters. The students are provided with a game board which is a plan of the schoolyard and visual elements to symbolize the interventions envisioned. By having already taken part in the game, the school community was already partly engaged with the idea of reshaping the schoolyard. In addition, the results of the game helped give insights to what were the communities values, challenges, and wishes associated with the place, based on the feedback shared by the students after playing the game it was possible to evaluate the most important factors to be taken into consideration.

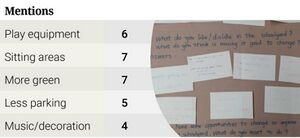

The students mentions for improvement based on the game:

· 6 mentions of more play equipment;

· 7 mentions of more sitting areas;

· 7 mentions of more green elements;

· 5 mentions of less parking;

· 4 mentions of including music/decoration.

Guided visit to the school

Before the application of the program, it was possible to have a guided visit of the schoolyard with the staff and other guests, in the visit it was pointed out some of the dissatisfaction of the students and some of the changes being considered for the future of the yard by the school administration. Among the topics raised, there was the discussion about the sports court, which the students dislike the appearance of, nicknaming it a cage; position, complaining it takes up a lot of open space in the yard; and the fact that it is also used as parking. When it comes to parking, the administration itself agrees there are more parking areas than is actually necessary, and there is a general agreement on the necessity to increase the green surface within the area.

Phase C: Collaborative Visioning and Goal Setting

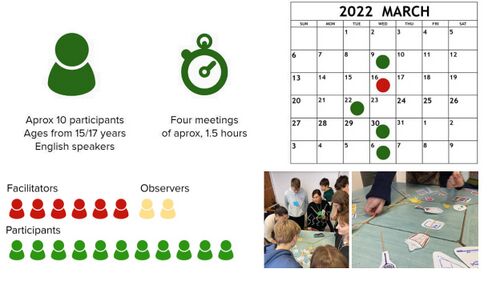

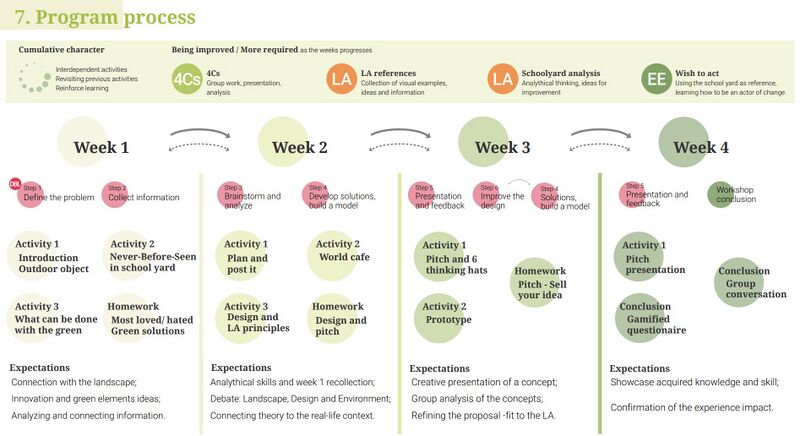

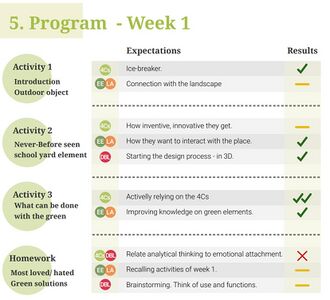

Method for program application:

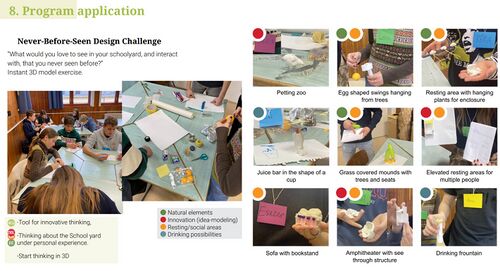

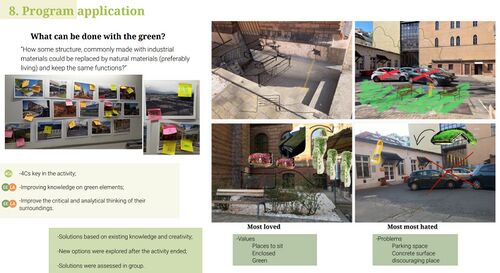

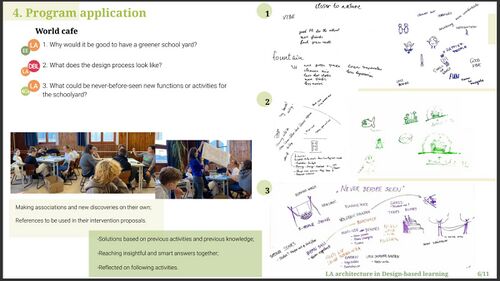

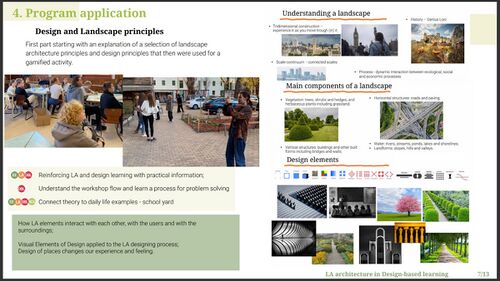

The program was formulated by breaking down the design process into three workshops, having the fourth meeting destinated for the conclusion of all the activities. Different tools were selected for each task to have a fun and rich experience that is linked to the landscape. The foundation of the program is to put the student as the main actor in each activity, giving them autonomy to make decisions and create, and also have an experience centered on practical activities, rather than in theory. Additionally, the program is place-based, in a way that the learning of information will happen through the association with the landscape. In this case, the landscape in focus is the schoolyard, and the proposals for improvement of the area should consider not only the students’ wishes and needs, but also apply the principles of LA and DBL. Another important principle of the program is its cumulative character, as the activities as interdependent and to reinforce the learning of the proposed information it is important to recollect what was used for previous activities. In this way improving practice and knowledge related to schoolyard analysis, LA references, Environmental Education, and soft skills.

The Scene in Your Story of Visioning

- The students need to participate more in the shaping of their learning environments

- It is needed to make it possible in an engaging and fun way

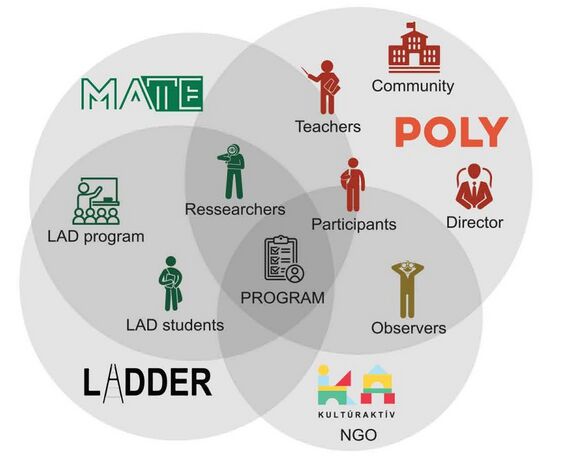

The Actors in Your Story of Visioning

Main actors:

- Students who responded to the call for action to participate in the workshop series

- LADDER/LAD and MLA tutors and students through mediating and tutoring in the workshop

Indirect actors:

- Schools’ board of directors

- Teachers

- Parents

The Story of Visioning

Program Goal: To have planned intervention(s) for an area within the schoolyard with a focus on increasing its green surface. Aiming for multifunctionality and sustainability using the DBL method and Landscape Architecture principles.

Through the course of the program the participants should learn about/improve:

- How to integrate green elements and surfaces into their ideas and how to do so using LA and Design principles.

- The positive effects of softscape in a living space.

- How to connect with the landscape (schoolyard) on a personal level.

- The design process concept.

- The 4Cs (communication, critical thinking, creativity, collaboration), experimentation, among other soft skills, as well as understanding mistakes as a part of the process.

- Have a collaborative vison for the schoolyard.

Strategy:

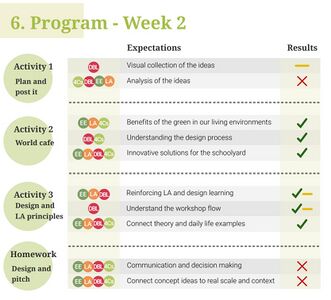

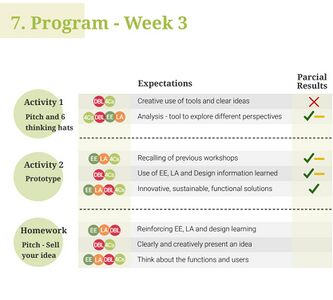

To achieve the goals the program was organized as it follows (picture)

Reflect on Your Story of Visioning

The most important points to formulating goals is knowing the needs and wants of the users, to be able to transform the area, we need to see it as the users do. Then, knowing the tools and knowledge at disposal, it is possible to fine-tune such ideas, to bring them to their best capacity. Using collective knowledge, experience, and discoveries.

It is all better when done collaboratively, connecting people and place, creating bonds, and improving the process together. A good vision is a shared vision, where all the stakeholders are represented, active, and engaged in the realization and maintenance of it.

Phase D: Collaborative Design, Transformation and Planning

The Action

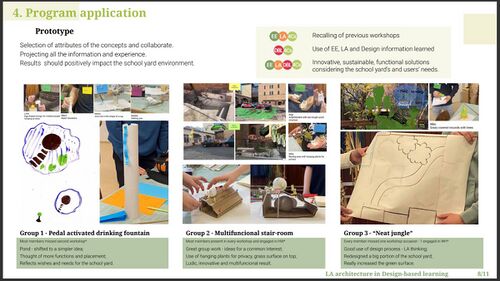

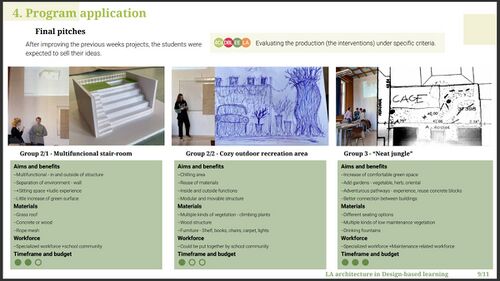

- Workshop application summary:

Reflect on the Action

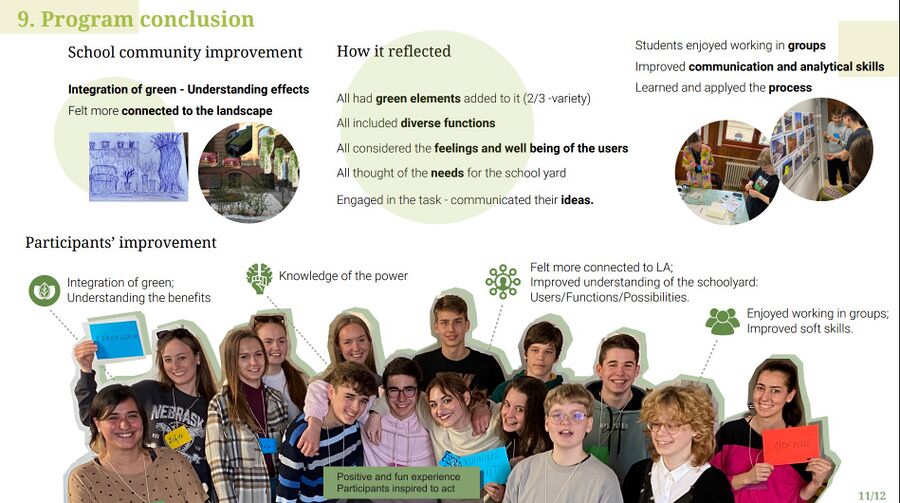

The work development indicated that the ideas increased in complexity but remained realistic and attended to the schoolyard’s needs, pointing to an increase in the understanding of the information provided and in critical thinking. The group work showed that the students had great communication and were able to achieve results under restrictive situations, such as the lack of material, but mostly the short time provided. The students also seemed highly motivated into realizing the interventions. “By now if the problem is the grass I can come and cut it myself,” said one of the participants of the neat jungle group (group 3 of the third and fourth weeks).

In summary, the results showed that all proposals had green elements added to them, the majority with a big variety, they considered the feelings of the users, varied functions, and the needs of the schoolyard. In addition, most of the groups were engaged in the task and managed to explain and exhibit their ideas with their tools of choice. The participants showed to be more prepared and motivated to improve the schoolyard situation and to have understood or enhanced the proposed learning: how to integrate green elements and surfaces into ideas; the positive effects of softscape in a living space; how to connect with the landscape on a personal level and to read and understand the disposition of elements; the design process concept; and development of soft skills. The improvement throughout the experience showed these results as valuable to completing the proposed activities.

Phase E: Collaborative Evaluation and Future Agendas

Collaborative Evaluation and Landscape Democracy Reflection

All the students expressed being satisfied with the experience overall, confirming it was a fun and positive event for all the participants. Even if not completing the whole process for the ideas and not making full associations between the content applied and LA and DBL knowledge, the students showed personal development between the first and the final meetings. Overall, the students appreciated the practical (action-based) character of the program, the same as being autonomous and working in groups.

All the students indicated to be very engaged in implementing their ideas, showing how simple actions of empowerment can generate big outcomes.

The Actors in your Collaborative Evaluation

Main actors:

- Students who responded to the call for action to participate in the workshop series

- LADDER/LAD and MLA tutors and students through mediating and tutoring in the workshop

Indirect actors:

- Schools’ board of directors

- Teachers

- Parents

Reflection on the Online Seminar

Reflection on your Living Lab Process

Through this work, an enhanced perception of the schoolyard was brought to the students. As of now, instead of seeing only the present situation with emphasis on the negative aspects of the yard, the students also see the potential for improvement, understand better the possible changes, have a collection of ideas and concepts that can be improved and applied, and maybe even more importantly, they know the positive outcomes coming from such changes. This collection of knowledge together with the realization of the power to improve an environment that reflects directly on one’s quality of life is the first step to raising the will to act for bigger future developments. Quoting Paulo Freire, “education won’t change the world. Education changes people, people change the world”.

Your Living Lab Code of Conduct

- Involvement of all kinds of users

- Get direct participation with the community

- Improve the environment of the school for and with the school community

- Motivate the school community to be an active user who knows how to shape the school environment in the future in a proactive way

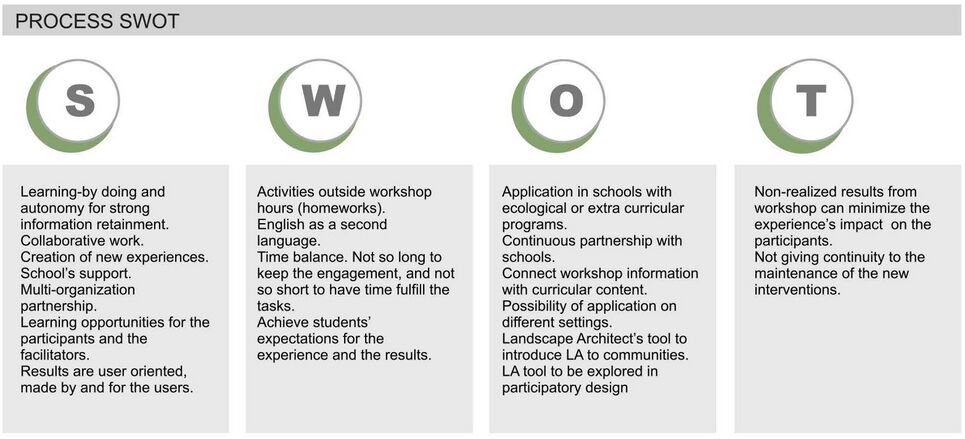

Process Reflection

Meaningful results:

- Cumulative aspect of the program was effective (improving the use of learnings and applying previously done assessments and ideas)

- Student engagement improved throughout the program and continued after its finalization.

- Solutions were realistic

- 4Cs (creativity, collaboration, critical thinking, and communication) were present in the entire process and improved throughout it

- Participants gave their insights on the process and helped identify the weaker aspects of it

Meaningful challenges:

- Short time for the accomplishment of the proposed tasks

- Lack of ideal structure/material on some occasions

- Disconnected from the schoolyard by the location of the activities

- Homework (and having the program relying on it)

- LAD students participating in the Living Lab before taking part in the online seminar (led to misunderstanding of the proposed tasks and lack of engagement)