LED Online Seminar 2018 - Working Group 9

--> Back to working group overview

Dear working group members. This is your group page and you will be completing the template gradually as we move through the seminar. Good luck and enjoy your collaboration!

Assignment 1 - Reading and Synthesizing Core Terminology

- You can read more details about this assignment here

- Readings are accessible via the resources page

Step 1: Your Landscape Democracy Manifestoes

Step 2: Define your readings

- Please add your readings selection for the terminology exercise before April 18:

A: Landscape and Democracy

The European Landscape Convention (Florence, 2000) Mariana

Burckhardt, Lucius (1979): Why is landscape beautiful? in: Fezer/Schmitz (Eds.) Rethinking Man-made Environments (2012)Mariana

B: Concepts of Participation

Burckhardt, Lucius (1974): Who plans the planning? in: Fezer/Schmitz (Eds.) Rethinking Man-made Environments (2012) Tanjila

David, Harvey (2003): The Right to the City, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Volume 27, Issue 4, pages 939–941 Tanjila

Sanoff, Henry (2014): Multiple Views of Participatory Design, Focus Navid

Hester, Randolph (1999): A Refrain with a View, UC Berkeley Vrain

Hester, Randolph (2006): Design for Ecological Democracy - Sacredness, The MIT Press Magdalena

C: Community and Identity

Nassauer, Joan Iverson (1995): Culture and Changing Landscape Structure, Landscape Ecology, vol. 10 no. 4. Tanjila

Hester, Randolph (2006): Design for Ecological Democracy, The MIT Press Navid

Welk Von Mossner, Alexa (2014): "Cinematic Landscapes" Magdalena

D: Designing

Hester, Randolph: Democratic Drawing - Techniques for Participatory Design Vrain

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2013): Places in the Making: How Placemaking Builds Places and Communities Navid

Hester, Randolph: Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Sustainable Happiness Vrain

Pritzker Prize-winning architect Alejandro Aravena on sustainable design and community involvement in Chile Mariana

Kot, Douglas and Ruggeri, Deni: "Westport Case Study" Magdalena

E: Communicating a Vision

Steps 3 and 4: Concepts Selection and definition

- Each group member selects three relevant concepts derived from his/her readings and synthesize them/publish them on the wiki by May 9, 2018

- Group members reflect within their groups and define their chosen concepts into a shared definition to be posted on the wiki by June 6, 2018.

- Other group members will be able to comment on the definitions until June 12, 2018

- Each group will also report on their process to come to a set of shared definitions of key landscape democracy concepts on the wiki documentation until June 20, 2018

Concepts and definitions

Author 1:Magdalena

1. Concepts o participation: Sacred Places - Prof. Hester (LA form US) aims to encourage the community/citizens, to participate into design process o their neighborhood. Sacred places are these areas and elements of the landscape to which the community has a strong conntection. These places can oten olny be identiied based on local knowlegde and experience. In design process, according to Hester, locals are asked to describe and map the "sacred structure" of their town. As an example, the "sacred structure" inspired the final plan to revitalize Manteo, small villige in North Carolina, US.

2. Design: Design participation according to Hester's Twelve Steps - community development framework consisting 12 points of design process, a.o. Listening, Setting goals, Acrivity Mapping, Introducing the Community to Itself, Confirming goals, Evaluation after Construction. As an example, this process was implemented in Westport, California, where a dialogue between designers and residents revealed a final design. As a result of this process, the residents of Westport received a community development project, which emphasized their needs for affordable housing.

3. Community and Identity: Cinematic Landscapes - using a real landscape in a film narration in order to expose the racial, gender, and economic power dynamics that led to the emergence of the actual crisis landscape. Example: Film "Beasts of the Southern Wild".

Author 2:...Mariana

1. The European Landscape Convention

Landscape policy : expression by the competent public authorities of general principles, strategies and guidelines that permit the taking of specific measures aimed at the protection, management and planning of landscapes

Landscape quality objective: formulation by the competent public authorities of the aspirations of the public with regard to the landscape features of their surroundings

Landscape protection : actions to conserve and maintain the significant or characteristic features of a landscape, justified by its heritage value derived from its natural configuration and/or from human activity

Landscape management: action to ensure the regular upkeep of a landscape, so as to guide and harmonise changes which are brought about by social, economic and environmental processes

Landscape planning : strong forward-looking action to enhance, restore or create landscapes.

2. Burckhardt, Lucius (1979): Why is landscape beautiful? in: Fezer/Schmitz (Eds.)

Landscape in Scenario 1: is a construct of different layers (visual, technological, natural, infrastructure) in a temporal dimension.

Landscape in Scenario 2: is an idealized image of phenomena resulting in a charming place.

Ruins in the Landscape: Symbol of past history, in landscape terms, erosion.

Beautiful Landscape: Construct comprised of conventional visual structures.

3. Pritzker Prize winning architect Alejandro Aravena on sustainable design and community involvement in Chile

3S : Phenomen divided in 3 main problems regarding Scale, Speed and Scarcity applied when people moving to cities.

The Design Purpose to understand and answer the 3S: To channel peoples own building capacity.

With the right design, susteinability is nothing but the regurous use of common sense

Participatory design : The attempt to find with precision what is the right question, and provide alternatives that are validated politically and socially. There is nothing worst than answering well the wrong question.

Design power of synthesis : To make a more efficent use of this cost-resources in cities, which is not money but cordination. Attempt to put in the most inner core of architecture the force of life

Author 3:Tanjila

- Burckhardt, Lucius (1974): Who plans the planning

Planning is determined by legislative issues and implicated in a social framework. The urban planner's sciences and auxiliary sciences such as urban geography, urban sociology, and planning theory, planning methodology and planning strategy have made advances in recent times. However, how they are applied depends always on the character of the person doing the planning. To reflect on urban planning means not to study the newest theories on housing density or traffic management, it is primarily a matter of giving much broader consideration to the ways in which local authorities make plans to change their environment.

- David, Harvey (2003): The Right to the City

The main endeavor of this book is to provide an anti-capitalist and revolutionary meaning, to the ‘right to the city’. A right whose meaning has however to be characterized. In this sense, the ‘right to the city’ not as a right that already exists, not as only a right to citizenship as it has been mostly understood, but as a collective struggle by all those that have a portion in producing the city and making the life in it, to claim the right to decide what kind of urbanism they are looking for. The collective labor that produces the city and its infrastructure, mostly builders and constructors, and those that create life in the city, various social and cultural groups whose activities and way of living enriches and produces city-life, are lacking the ‘right to the city’ because of the prevailing of capitalist urbanization.

- Nassauer, Joan Iverson (1995): Culture and Changing Landscape Structure

This paper is focused on four different 'cultural principles for landscape ecology'. First comes human landscape perception, cognition, and values that directly affect the landscape. Secondly, cultural conventions which powerfully influence landscape pattern in both inhabited and apparently natural landscapes. Then, cultural concepts of nature which are different from scientific concepts of ecological function and finally the appearance of landscapes which is responsible for communicating cultural values.

Author 4:Navid

- .Sanoff_Multiple views of participatory design

Participatory design : is an attitude about a force for change in the creation and management of environments for people. Its strength lies in being a movement that cuts across traditional professional boundaries and cultures.

collective intelligence (CI):s based on the ability of groups to sort out their collective experience in ways that help to respond appropriately to circumstances - especially when faced with new situations.shared insight that comes about through the process of group interaction, particularly where the outcome is more insightful and powerful than the sum of individual perspectives.

PROMOTING PARTICIPATION : By • Establishing a policy of inclusiveness • Holding open meetings • Making speeches to community groups • Obtaining public input • Making public announcements • Holding face-to-face meetings • Conducting progress surveys

- Hester - Design For Ecological Democracy

There are 3 fundamental issue to ecological democracy :

1- our cities and landscapes must enable us to act where we are now debilitated.

2- our cities and landscape must be made to with stand short term shockes to which both are vulnerable .

3- our cities and landscape must be alluring rather than simply consumptive or conversely , limiting.

- Places in the making MIT

Placemaking is a critical arena in which people can lay claim to their “right to the city.” The fact that placemaking happens in public spaces, not corporate or domestic domains, is a critical component to its impact on cities. Public places, which are not our homes nor our work places, are what Ray Oldenburg calls “third places.” Placemaking creates these “third places” that he describes as, “the places of social gathering where the community comes together in an informal way, to see familiar and unfamiliar faces, somewhere civic discourse and community connections can happen. Placemaking is an act of doing something. It’s not planning, it’s doing. That’s what’s so powerful about it. Barrier of placemaking : 1. Making the case for placemaking is harder than it should be. 2. “Making” takes time in a “here and now” culture. 3. Expertise is a scarce resource. 4. It’s hard to know who to involve—and when and how to involve them. 5. Placemaking exists in a world of rules and regulations. 6. Reliable funding sources are scarcer than ever. 7. There’s no glory in the postmortem

Author 5:V.D.

A refrain with a view: Hester Randolph

Balancing decision

Local participation enables the sense of community, surmount environmental injustices and give a voice to the locals. It provides support, carrying and realism to decision-makers and stakeholders.

Techniques for Participatory Design: Hester Randolph

Representing

This concept is about is representation techniques to create space with people by using democratic drawing, based on five fundaments: Representing people, exchanging professional knowledge and local wisdom spatially, coauthoring design, empowering people to “represent” themselves, and visualizing deep values such as community, stewardship, fairness and distinctive place. In a way, planners are the facilitators of representation, in participatory design.

Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Sustainable Happiness Randolph Hester

Enabling Form In participatory design keys to success are sacredness, sharing experience, caring, connectedness and simply to be what we are.

- ‘’Sacredness’’: ‘’Sacred place are key to sustainability’’, sacredness pulls us towards sustainable decisions and actions.

- ‘’Shared Experience’’: Communities must take a collective decision.

- ‘’Caring’’: through discussion and debates citizen shows care and attention to environmental issues.

- ‘’Social connectedness’’ is a key point to a peaceful sustainability and to social justice.

- ‘’To Be What We Are’’: Avoid losing social identity and background, being comprehensive is essential, simply bring up for the sense of place.

Step 5: Reflection

According to our readings, Landscape democracy is a concept for transforming a living space in a complex process, where the society plays a major role. Planning and implementation are carried out with the direct participation of citizens from different age and social groups because the landscape is a common good.

Landscape democracy is a collaborative phenomenon and the process of engaging people's profit into design through asking their opinion, improving their economic and social situation and placemaking and its main factor is citizen's participation.

Also, it is an organic process with the aim to create spaces for the people and by the people, where the active participation of the involved actors is the backbone to create, preserve or improve the place that is being under consideration because of its important spatial and symbolic value to the community. It is set by legislative issues and implicated in a social framework which is determined by urban geography, urban sociology, and planning theory, planning methodology and planning strategy and how they are applied depends on the character of the person doing the planning. Landscape democracy can be focused on four different cultural principles for landscape ecology-

1. Human perception, cognition, and values that directly affect the landscape.

2. Cultural conventions which powerfully influence landscape pattern in both inhabited and apparently natural landscapes.

3. Finally the appearance of landscapes which is responsible for communicating cultural values.

To conclude, Landscape Democracy result from planning and design in which citizens participate equally in the formulation of a coherent and fair proposal. By defining collective rules landscape democracy involve people and including them as part of the decision process. The collective interests surpass cultural and social differences and promote linking people to the environment.

Step 6: Revised manifestoes

- please look again at your initial manifestoes and update them with any new aspects/prespectives you have taken up during this seminar

Assignment 2 - Your Landscape Symbols

- You can read more details about this assignment here

This is a new picture (one week ago) from "Mellat Park", where is the main and the biggest green space in Mashhad,my hometown, as a second metropolitan in IRAN. [ Mellat means people in English language]. This public place locate in the center of Mashhad and provide a suitable arena for people to walk, play,recreate and interact and is a pure landscape symbol in Mashhad.

This a Eram Palace in Shiraz with its valuable history, where is famous because of its well-known poet in the world. Shiraz was a capital of ancient Iran and there was a palace of that dynasty. The garden around the building is a memorable public park in the scale of the country and its note standing Cedar, which is pictured here, became a famous tree as a” Naz Cedar”. today, Eram Garden and building are within Shiraz Botanical Garden (established 1983) of Shiraz University. They are open to the public as a historic landscape garden. They are World Heritage Site, and protected by Iran's Cultural Heritage Organization.

Dowlatabad Garden located in Yazd, central Iran, is a Persian architecture jewels.The Garden is an authentic Iranian garden that annually attracts thousands of domestic and foreign tourists.This traditional air-conditioning system of local houses around the desert in Iran is the essential elements at the residential structures. However, the exaggerated grand size of this wind catcher functioDowlatabad is among the Persian gardens that have just been registered on UNESCO's World Heritage List as one of the masterpieces of traditional gardens.ned perfectly well. The Persian garden was registered on UNESCO’s World Heritage List on Monday (June 26th).The decision to register the property on the list was made during the 35th session of the World Heritage Committee, which opened in Paris on June 19.

Landscape Symbols Mariana Martinez Cairo: ...

"The Square of the 3 Cultures" is a space in Mexico City with an important cultural, historical, political and architectural value. The name "3 Cultures" is in recognition of the 3 periods of Mexican history reflected by buildings in the plaza: aztec ruins (ca.1400), Spanish colonial(1600), and a massive housing complex (1964). In addition to this...the open space and surroundings of this square are a memorial to the students and civilians killed in this square by military and police in the so called "Tlatelolco Massacre"(1968) after their demonstration against the oppressive government.

Monumento a la Revolución (Monument to the Revolution)Republic Square, Mexico City. Landmark, reference, gathering point, element of historical celebration, symbolic triumphal arch, public space, architectural element. The Monument to the Mexican Revolution is all of them. It's symbolism lies in it's historical and spatial importance to the mexican people.

Zócalo de la Ciudad de México (Mexico City Main Square) GeoLocation: Downtown, Mexico City The most important open public space in Mexico City. People identify it as an element of cultural heritage, reunion, the iconic point to express themselves, celebrate, grieve and share as a community. In the political, cultural and social atmosphere it is used for all the purposes taht involve the mexican people.

Landscape Symbols Auther 3: V. D.

Hillscape. The village of Kospallag is located in the north of Hungary in the Pest county. This image represents a view from a window to a hill. Hills are stong landscape symbols that are taken as an icon of regional identity. Also, it provides a certain view of the surrounding, the hill itself is an element of the landscape and a part of a culture. Berries harvesting, wood collecting, and other practice are linked to it.

Riverscape. We can distinguish easily one of the landscape symbols that shaped the Carpathian basin landscape, the Danube. Its water reflects the landscape, from the countryside to the inner city. Water is a landscape symbol which can be found in many aspects of the Hungarian culture and history: baths, river transport, riverbanks and sports practice.

Landscape Symbols Author 4: Magdalena Giefert

This is a monument of John Paul II (Poland, city of Olsztyn). From the historical and socio-political point of view, he played a great role in Poland. Above many other issues, he supported the transformation of Poland to become a democratic country. The regard and affection in which the people of Poland held and continue to hold John Paul II is extraordinary (in 1979 during his first visit as a pope, 13 million of Poles saw him in person). Before he died in 2005, there were 230 statues of him in Poland and after his dead this amount lifted to ca. 550 (there are about 200 monuments in other parts of the world overall). Monuments are well recognized and understandable, located in central parts of parks, squars, public areas. Are used by the public mainly as gather points to worship and memorialize. Picture taken in 1995, Olsztyn, Poland.

Today nearly 12 million people in Poland live in prefabricated buildings. This panel system entered the our market in the late 80’s and had a major influence on the landscape in every town. There are thousands of settelments which were built with this technology and embrace 3 generations of residents. It is a part of our history, symbol of economic and menthal change of our society. The strucure of settelments is usually the same, including green infrustruction and leisure parts, like if the planners used "copy-paste" tool. Photo taken in Szczecin, 2005, Pomorzany Estate.

Local symbol. I would call it "Our Lake". Lake Sarcz in my Town of Birth, Trzcianka, Poland. Meeting - and leisure area for many generations. It's still a primary location for many individual and social activites. Still pure on one side but regulary visited. Beloved, important, accesible, used and shared by people. Considered as an important part of local landscape, which makes it complete. Photo taken in 2002.

Landscape Symbols Author 5: Tanjila Tahsin

"Shakhari Bazaar" shares a long history more than 400 years with Dhaka city itself. It is one of the oldest localities of Dhaka city, located near the inter-section of Islampur road and Nawabpur Road - the two main arteries of the old city. For centuries Dhaka has been famous for its traditional arts and crafts. The name implies that the area began as a settlement of "Shakharis" or a community of craftsmen specialized in making conch shell ornaments.The buildings of Shakhari Bazaar trace the history and evolution of building crafts, construction and materials of Dhaka for the past few hundread years. Lack of maintenance and repair has resulted in a worn out appearance. Shakhari Bazaar lined with thin slices of richly decorated brick buildings, built during the late Mughal or Colonial period.

“Dhanmondi Lake” is a lake located in the Dhanmondi residential area in the center of the Dhaka city. The lake was originally a dead channel of the Karwan Bazar River, and was connected to the Turag River. In 1956, Dhanmondi was developed as a residential area. In the development plan, about 16% of the total area of Dhanmondi was designated for the lake. Dhanmondi Lake development was an attempt to embody an urban oasis to provide relief in the concrete cityscape. The concept was to invite people to protect the lake from encroachment creating a buffer zone in between the allotted residential plots and the lake. Now, Dhanmondi Lake has become a well visited tourist spot, with cultural hubs such as the Rabindra-Sarobar located along its side.

Cox's Bazar Beach, located at Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, is the longest unbroken sea beach in the world. Cox's Bazar is the prime beach and tourist town in Bangladesh, situated alongside the beach of the Bay of Bengal, beside the Indian Ocean, having unbroken 120 Kilometer golden sand beach. This town is situated in the Chittagong Division in south-eastern Bangladesh. Cox's Bazar is a city, fishing port, tourism centre and district headquarters in Bangladesh. This is the most visited place in Bangladesh, with its beautiful refreshing green hills, traditional boats and the wonderful sea beach. Over many years Cox's Bazar has been an attraction to both international and domestic tourists. Opportunities of bathing and swimming in shark free warm water makes Cox’s Bazar a top tourist attraction.

Assignment 3 - Role Play on Landscape Democracy "movers and shakers"

- You can read more details about this assignment here

Assignment 4 - Your Landscape Democracy Challenge

- You can read more details about this assignment here

- Each group member will specify a landscape democracy challenge in his/her environment

- Each Landscape Democracy Challenge should be linked to two or three of UN's 17 sustainable development Goals

- 17 Shahrivar pedestrian way - Tehran- Iran

caption: why did you select this case? This is kind of top-down decision making, which was done from tehran municipality without people and users's attitude and participation.Government banned the street for cars to improve environmental properties but the result is kind of economic Recession for stores, which mostely based on cars.

- Yourname challenge 6.jpg

caption: UN's Sustainable Development Goal?

Your references:'

- sustainable Development Goals (https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/)

- Personal Studies

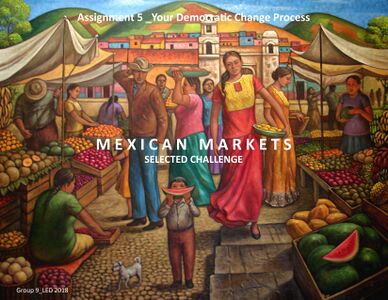

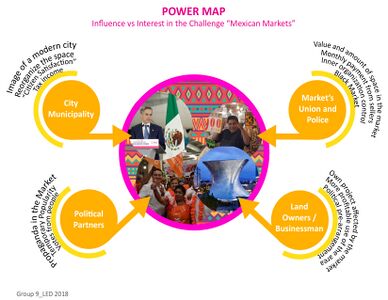

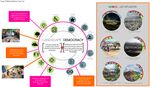

Landscape Democracy Challenge 2 -Mariana Martinez Cairo Cruz

- MEXICAN MARKETS: IMPROVISED PUBLIC SPACES

why did you select this case? Public Open Spaces Markets in Mexico represent now a day two radical opposites. In one hand, they are the gathering space, they have not only cultural but also an economical importance in our society. They contribute in peoples cultural identification to their community. However, in spatial terms, they are major urban and lanscape challenges. They are not properly planned, organized and managed. They highly contribute to polution in the area and mobility problems.

The lack of planning to make this markets integrate properly to the landscape and urban environment. People that both, work and consume, from this public spaces have, most of the times, to develop their own elements to use the space. The result of this affect the quality of the space, the environmental impact of this, the economy of the market itself and other spaces around it, the quality of the products (specially food) that it's sold in there.

Open spaces, recreational areas, landscape in general is mainly afected by the unplanned presence of this markets. They support the uses, life and activities of this spaces by providing food, souvenirs, etc to the users. However, the lack of organization and normalization of them create visual chaos, pollution, direct impacts in the functionality of the open space (invading bike roads, streets, obstacles to main entries, damaging vegetation)

caption: The government, with the task of regulating the functionality of the markets, urban planners and designers, into creating adequate spaces for them, and mostly important, the people, whom in teamwork with the planners and government should provide the information about they needs into this spaces, which , ultimetly, they will use.

The UN's goal suitable for this landscape challenge is : "Goal 11: Make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable" In this case, Mexico city sometimes enables people to advance socially and economically. Because of its rapid expansion, growth, and lack of proper planning. However, there is a big opportunity also into creating and mantaining jobs through activities in markets, due to their cultural, historical and identification importance. Markets have been and always will be part of Mexico. But for them, the right infrastructure is needed.

Your references:

- Suitable Development Goals by United Nations www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

Landscape Democracy Challenge 3 Tanjila

- Preserving open public spaces in Dhaka for recreation, livability and identity

caption: why did you select this case-Public spaces breathe life into the social fiber of a community. It is the open markets, plazas, parks and squares and high streets that give respite to city dwellers from the daily hustle and bustle of city life.People gathering to watch a street magician, women socializing at the local fruit market, men sipping tea by a small lake-such are the scenes of a city that nurtures and values its urban environment and makes the public space accessible to city dwellers. But in Dhaka, such glimpses of free contact and spontaneous movement of people are rare in the public space which in reality has become somewhat of an eyesore: roads choked with traffic, piles of garbage discarded in the open, street sides occupied by hawkers, poorly maintained buildings, etc.

caption: what is the issue/conflict - Poor management of formal open space one of the key issue of this conflict. Physical quality of open spaces is very poor in Dhaka. The existing parks and play grounds are not properly maintained by authority. Although the country is very much green, much of the open spaces are found barren and repulsive. The contribution of open space, as a physical element, focuses on three criteria: quantity, quality and accessibility. But most of the open spaces in Dhaka do not fulfill all the three criteria.

caption: what is the issue/conflict (2)- Lack of preservation efforts is another key issue. Water bodies and lakes are also included to turn into recreational areas considering their scenic beauty and shortage of open space in reality. But by dumping waste people are hampering the aesthetic beauty and maintenance of these lakes and water bodies. On the other hand, unwanted and incompatible land uses are being developed around the historical sites. This is a serious threats to heritages.

caption: who are the actors? - Vacant lands, green open spaces and low lying areas of Dhaka are being illegally occupied by slums and squatters. Moreover, private owners are also taking the adjacent open spaces illegally. Such cases are found near Dhanmondi Lake, and Gulshan Lake. Some of the areas designated as retention ponds and drainage channels in the flood protection schemes are also being filled up by real-estate developers.

Your references:

- Suitable Development Goals (https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/)

Landscape Democracy Challenge 4 : Magdalena Giefert

- Secured housing estates in Poland

The phenomenon of gated and guarded neighbourhoods in Poland ist well known and discussed. The number of secured housing estates grows and what makes it bothering, they are often being fenced and detached from the surrounding. This need of living in gated estates had been artificially created mostly by investors, who made people believe, that such a surrounding refers to their expectations and sense of comfort. Guarded neighbourhoodss not always offer additional functions to their inhabitants, but the security option became the most basic and arresting feature.

A public space is a social space that is open and accessible to all, regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, age or socio-economic level. Existence of gated estates undermines the real meaning of public spaces. It causes isolation, discriminations on various levels (a.o. Social categories) and a lack of balance in a spatial dimention. Is it only a need to live in a secured, safed neighbourhood or is it “the process of creating elites through the use of the urban"? Discussion continues.

The idea seems to be decent. According to guarded estates in US, gated neighbourhoods schould correspond to their functional or organisational parameters, but also to inhabitants’ characteristics and motivations (e.g.lifestyles, interests). However, in Poland the reasons for living in gated neighbourhoods caused by the need for security could be a result of existing “culture of fear” and some kind of egoism. Instead of suppressing this process, it has been developed.

There are main two groups of actors in this process: Investors/Developers and their Clients. Population has decreased, people are struggling with finding a proper accomodation. Although the answer for this need has been bastardised, there are many fans and supporters of gated estates. The key to freedom/independence doesn't suit to the original image of community. The lanscape becomes more and more privat and limited, therefore the social space loses its natural meaning and it is beeing transformed into protected/artificial space.

Goal 11: Make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable. The goal for this challenge is to make a balance between economic and social development. Adequate housing means also a healthy, social surrounding accessible for different groups of people. To this challenge also refers the Goal 3: good health and weel-being, where the psychological aspects (e.g. isolation) have to be taken into consideration.

Your references:

- Suitable Development Goals by United Nations www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

Landscape Democracy Challenge 5 V.D.

- Cities for everyone

Who are the actors? In Budapest, since 2013, the government, politicians and municipality decide to reshape the image of the historic part of the city as an idealistic modern city with shopping streets and beautiful squares. This urban renewal has been launched with a lot of political communication in order to keep this part clean and accessible to the lucky few the city decided to protect this historic area by setting up a forbidden zone for homeless

What is the conflict? From the early time of the gellért hill park at the end of the 19 th century, the park design gave a strong image to the city. Later in the 1930’s a whole workers district has been demolished to extend the park. Indeed gentrification process has begin and are emphasized by tourism. In the past decades, some part of the green space has been abandoned and left some voids for the marginalized. (due to a potential new project)

Thus the challenge is to take into account all users and potential one of city spaces in the context of a renewal.It is essential to landscape democracy to enable resilience by preserving the right to the landscape for all, freespaces and access to basics ressources (water, fruit tree…). Parks and public space are the social buffers that are key places for social resilience.

References:

- https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/poverty/

- https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/cities/

- https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/inequality/

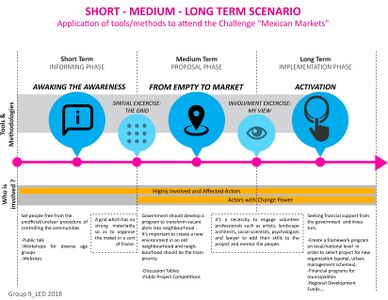

Assignment 5 - Your Democratic Change Process

- You can read more details about this assignment here

- After documenting and reflecting on your challenges you will continue jointly with one of these challenges and design a democratic change process

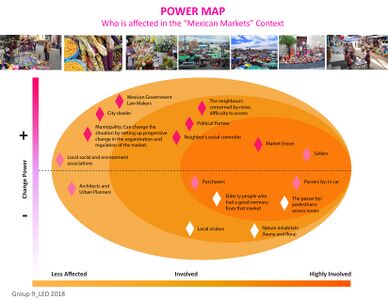

Your Democratic Change Process

- Mexican Markets_Selected Challenge

Reflection

- The traditional and new forms for the local economy to use public spaces represent a challenge and an opportunity to improve city life.

- It is clear that the current Mexico City government lacks the capacity, both technical and institutional, to generate a participatory decision-making process.

Conclusions

- It is essential to create an initial "Awareness" before taking into action any spatial or social driven-by-proposal

- Highly affected actors should be integrated in improvment processes , just as high change power actors should be committed and guiding these processes.

Your references

- http://www.mexicanisimo.com.mx/mercados-mexicanos/

- https://gehlpeople.com/books/favour-public-space/

![This is a new picture (one week ago) from "Mellat Park", where is the main and the biggest green space in Mashhad,my hometown, as a second metropolitan in IRAN. [ Mellat means people in English language]. This public place locate in the center of Mashhad and provide a suitable arena for people to walk, play,recreate and interact and is a pure landscape symbol in Mashhad.](/images/thumb/8/8c/LED_Landscape_Symbol-navid_Asadi_-.jpeg/112px-LED_Landscape_Symbol-navid_Asadi_-.jpeg)