LED Online Seminar 2019 - Working Group 4

--> Back to working group overview

Dear working group members. This is your group page and you will be completing the template gradually as we move through the seminar. Good luck and enjoy your collaboration!

Assignment 1 - Reading and Synthesizing Core Terminology

- You can read more details about this assignment here

- Readings are accessible via the resources page

Step 1: Your Landscape Democracy Manifestoes

Step 2: Define your readings

- Please add your readings selection for the terminology exercise before April 24:

A: Landscape and Democracy

Burckhardt, Lucius (1979): Why is landscape beautiful?: Fezer/Schmitz (Eds.) Rethinking Man-made Environments (2012) (Anna Fernanda Volken)

B: Concepts of Participation

Day, Christopher (2002): Consensus Design, Architectural Press (Adriana Tredici);

Hester, Randolph (2005): Whose Politics (Arati Amitraj Uttur)

C: Community and Identity

Welk Von Mossner, Alexa (2014): Cinematic Landscapes, In: Topos, No. 88, 2014. (Anna Fernanda Volken); Woodend, Lorayne (2013): A Study into the Practice of Machizukuri (Arati Amitraj Uttur)

D: Designing

Hester, Randolph (2006): Design for Ecological Democracy - Everyday Future, The MIT Press (Adriana Tredici);

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2013): Places in the Making (Arati Amitraj Uttur)

Salgado, Mariana, et al. (2015): Designing with Immigrants (Anna Fernanda Volken)

E: Communicating a Vision

A toolkit for transforming abandoned spaces through the arts. https://issuu.com/mahatat/docs/toolkit_en._final_issuu (Adriana Tredici)

Steps 3 and 4: Concepts Selection and definition

- Each group member selects three relevant concepts derived from his/her readings and synthesize them/publish them on the wiki by May 15, 2019

- Group members reflect within their groups and define their chosen concepts into a shared definition to be posted on the wiki by June 12, 2019.

- Other group members will be able to comment on the definitions until June 30, 2019

- Each group will also report on their process to come to a set of shared definitions of key landscape democracy concepts on the wiki documentation until July 12, 2019

Concepts and definitions

Author 1: Arati Uttur

A Study into the Practice of Machizukuri:

• Japanese practice of community building was startd in 1960s and 70s

• Some neighbourhoods in England have adopted these practices recently

• Comparisions drawn between Japanese and English neighbourhood demographics

• Studies made in various Japanese locations, by following several research planning objectives before the visit to the various locations was made.

• Machizukuri is used to address a wide range of local issues. There is evidence of strong relationships within communities and local governments. There are also other relationships between communities and Neighbourhood Associations, NPOs, academics, professional planning consultants and architects. There is also evidence of some familiar issues regarding difficulties in relationships within communities, between communities and local governments and between communities and the private sector. There is evidence that machizukuri does empower communities and is aiding the evolution of power to the local level, however, there is also evidence that communities in Japan have on the one hand had greater autonomy in some respects than their English counterparts for many years and on the other, have an inherent strength as a result of cultural and historical factors. Certain types and aspects of machizukuri have similarities to Neighbourhood Planning and machizukuri as a whole relates to activities that are considered to represent Localism in England. There are a number of lessons that can be galvanised from the findings and experiences in Japan resulting from this study.

Places in the Making:How placemaking builds places and communities : Massachusets University

• Department of Urban Studies and Planning (DUSP) at MIT has consistently been rated the premier planning school in the world. Their mission is to educate students while advancing theory and practice in areas of scholarship that will best serve the nation and the world in the twenty-first century, by appyling advanced analysis and design to understand and solve pressing urban and environmental problems.

• Today’s place-making represents a comeback for community. The iterative actions and collaborations inherent in the making of places nourish communities and empower people.

• Place making started in 1960s and began as a reaction against auto-centric planning and bad public spaces. Now it has evolved to include broader concerns about healthy living, social justice, community capacity-building, economic revitalization, childhood development, and a host of other issues facing residents, workers, and visitors in towns and cities large and small. The practice aims to improve the quality of a public place and the lives of its community in tandem.

• Place making is an act of doing - not planning.

• Common challenges of placemaking :1. Making the case for placemaking is harder than it should be. 2. “Making” takes time in a “here and now” culture. 3. Expertise is a scarce resource. 4. It’s hard to know who to involve—and when and how to involve them. 5. Placemaking exists in a world of rules and regulations. 6.Reliable funding sources are scarcer than ever. 7.There’s no glory in the postmortem.

• The success of placemaking is the ownership shown among the project leaders and also the ownership the community shows towards its space. Avoiding procrastination and attacking any issue head-on seems to be the approach with this method.

Hester: Who's Politics

• As a landscape architect it is inevitable to have a political stance and not be involved in politics.

Author 2: Adriana Tredici

A toolkit for transforming abandoned spaces through the arts.

• Project by the "Mahatat" initiative based in Cairo. They develop a Toolkit (means step by step guidelines) , according to their own experience, for reactivating abandoned spaces in the sense of giving artists a place to present their work. "Abandoned spaces" means here lost buildings, public places that are not used anymore or simply lost corners.

• Giving back those lost places to the people, to the city, and making art seen for everybody for FREE. "INCLUSION" is an important word here.

Day, Christopher (2002): Consensus Design

• democracy works for politics but not for building a house; it means making compromises and designing a house doesn´t work by making those;

• consensus instead of democracy

Hester, Randolph (2006): Design for Ecological Democracy - Everyday Future

• designing for what people do all day: Observation of everyday urbanism.

• different users as a result of new time changes: Integrate future uses. (Conflicts between older and younger).

• some things stay in times of changes: Marking time. "Higher-density mixed-use neighborhoods seem to be more acceptable when decorated in tradition."

• clear statement of what people do and need. Everyday patterns integrated into visionary future: Design inspired by everyday life.

Author 3: Anna Fernanda Volken

Burckhardt, Lucius (1979): Why is landscape beautiful?:

• Landscape is a construct: to be found not in environment, but in the minds eye of those who look - a creative act brought forth by excluding and filtering certain elements, which is influenced by our educational background.

• Landscape is oriented: it is aligned to the ideal of the charming place created by painting/literature or tourism brochures and advertisements. This is the synonymous to filter out whatever we actually see to be able to integrate the outcome in our preconceived and idealized image of the charming place.

• Landscape is an artistic term: it is a constructed comprised of conventional visual structures.

Welk Von Mossner, Alexa (2014): Cinematic Landscapes, In: Topos, No. 88, 2014.

• Lanscape: is a space that is carefully constructed, not only through the selection of suitable filming locations but also through the way in which the images are framed by the camera.

• The setting: the cinematic environment which provides the space where the action takes place.

• Slow violence: a process of delayed environmental destruction that is dispersed across time and space, both geographical and socio-economic boundaries in nature.

Salgado, Mariana, et al. (2015): Designing with Immigrants

• The tree-of-life tool: a longstanding tool in narrative therapy and community work - a way to enable vulnerable people to speak about their lives in order to feel stronger.

• Participatory design: involving different groups of people in design processes - emphasizing the designers' responsibility for social inclusion.

• "Making together": the process of making people use their hands for externalising and embodying thoughts and ideas in the form of artifacts.

Step 5: Reflection

Since landscape is an ingredient not just found in the environment, but that which takes shape of the creative acts of the humanity that also uses it, the planning process has to be inclusive of the community just like any other customary tradition.

The creativity is filtered by elements that are influenced by our educational background, culture, and involvement. Such iterative actions bring humanity on a collaborative stand and further nourish the community while empowering the people. And that is why we should discuss how we interact with our landscape with different kinds of people, which emphasizes the designers' responsibility for social inclusion.

As a result we get to look at a democratic landscape in the true sense that will be resilient toward the power it gives and gets back from the community that uses it and takes charge of it. The built landscape that surrounds us all is used by us humans, it was designed for us and by us!

Step 6: Revised manifestoes

- please look again at your initial manifestoes and update them with any new aspects/prespectives you have taken up during this seminar

Assignment 2 - Your Landscape Symbols

- You can read more details about this assignment here

Landscape Symbols Author 1: Arati Uttur

Highway Dynamics: The highway is one such infrastructure element that faces some of the most raw and harsh natural elements and are constructed to withstand tests of time. Highways help us connect. They carry us across boundaries. They provide experiences.Bangalore 12.9716° N, 77.5946° E . Belgaum 15.8497° N, 74.4977° E. Ladakh 34.847°N 76.827°E.

Water:Water is symbolic to humans primarily in terms of existence.Due to this basic need, Water then becomes an integral part of cultural activities, focal point of urban developments, a contributing element for climate control etc.We also connect with water spiritually and seek refuge in its calmness. We also seek refuge from its power.12.9716° N, 77.5946° E

Sunrise and Sunset:The sun has utmost importance in many aspects of symbolism. Right from early civilisations and religious connections to modern day solar energy.However, the phenomenon of the sunrise and sunset hold a special place in landscape symbolism . They signify time and also dimensions in time. Symbolic to the beginning and the end. 26.9157° N, 70.9083° E

Landscape Symbols Author 2: Adriana Tredici

The Basilica San Petronio in Bologna was built in the year 1388 and got his effectiveness from january 1389. It is located in the very center of Bologna, with its main facade, unfinished, facing the Piazza Maggiore. Dedicated to the holy San Petronio (Bishop between 431 to 450) as a thanking for recovered freedom of the city. For this reason, the church was built since the beginning not as Cathedral, but as a civic and votive temple. As an opportunity for the people to show their devotion to the city it has been also the forum for demonstrations of public religiosity and citizens´spirit. It is the architectural expression of a new beginning of the city history and also and expression of identity of the city and its citizens. 44°29'36.5”N 11°20'35.6”E

As a result of a high urban migration and arrival of students the porticos in Bologna where built to extend the inner living space. At a certain point the streets where so crowded of porticos that they became a public space. Now this public space, built from a functional point of few is now an important space of human interaction with also a lot of cafés, bars, restaurants and shops. Protecting also from rain and sun. 44°29'37.6”N 11°20'26.9”E

This Piazza, Piazza Santo Stefano, is just one example of many more here in Bologna. First special thing about those places is the fact that in this old, dense city there is just a free, shaded spot surrounded of buildings. Built freedom. Public spaces, without the need of paying entrance where people can interact and their freedom to do whatever the want to: sing, dance, enjoy markets, chilling in the sun etc. 44°29'32.1”N 11°20'53.6”E

Landscape Symbols Author 3: Anna Fernanda Volken

Picture 1: 48°44’32.85”N 9°18’27.80”E I chose the old Rathaus because, first of all, it is an imposing building in the historical city center of Esslingen - which contains some of the oldest constructions in Germany. That is possible thanks to fact that the city suffered no significant destruction during the Second World War - so it can be seen as an "architecture resistence symbol" through times of bombs and suffering. I see it also as an expression of a local identity. The Old Rathaus was built around 1420 and it has an eagle on its top, the animal that symbolizes freedom. On the occasion of a renovation, in 1926, there were expressive donations by the citizens - showing the importance of the building to local people.

Picture 2: 48°44’35.51”N 9°17’38.76”E The vineyards offer interesting views over the trajectory of the train to/from Stuttgart and awaken a desire to try the local wines. Besides that, this landscape provides the basis for recreational opportunities, like the Vineyard Walk, when people really interact with the landscape.

Picture 3: 48°44’43.19”N 9°18’35.38”E Esslingen Castle is a preserved part of the medieval city fortification, which is located above the former and present-day city center. I chose the beautiful view it offers and it is important to say that the entrance is free, which invites not only visitors but residents to just enjoy a nice walk.

Assignment 3 - Role Play on Landscape Democracy "movers and shakers"

Jon Jandai : Co-founder of Pun Pun Center for Self-reliance in Thailand (Arati Uttur)

Sonja Hörster (Adriana Tredici)

Giancarlo de Carlo (Anna Fernanda Volken)

- You can read more details about this assignment here

Assignment 4 - Your Landscape Democracy Challenge

- You can read more details about this assignment here

- Each group member will specify a landscape democracy challenge in his/her environment

Landscape Democracy Challenge 1: Arati Uttur

- Give a title to your challenge

caption: why did you select this case?Although there may be arguments that question the sustainability of organic farming, there exist farmlands that are thriving on organic farming as they have followed some basic methods to cultivate and convert their lands into sustainable organic farms. Inorganic farming will only lead to long term damage. The sooner we realise this and take action, the faster we grow towards a sustainable future.

caption: what is the issue/conflict (2)Although UN India sustainability goals show a dedicated sector to end hunger and support sustainable agriculture, neither organic or inorganic farming have been given due importance by practical support from the government. Farmers continue to suffer through drought, poor crop quality and harvest issues.

Your references:

- ...http://www.ipsnews.net/2015/01/organic-farming-in-india-points-the-way-to-sustainable-agriculture/

- ...https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/agriculture/india-has-the-highest-number-of-organic-farmers-globally-but-most-of-them-are-struggling-61289

- ...http://in.one.un.org/page/sustainable-development-goals-a-handbook/

Landscape Democracy Challenge 2: Adriana Tredici

- Trees instead of concrete

caption: why did you select this case: I am from germany, I also live in a big city where housing is limited, rents are too high and the topic of climate change is still not integrated enough into urban planning. More living space in the sense of housing is important, but this issue should not be more important than „livable space “ in the sense of a „green city“ instead of “grey city”. And also Berlin is not only about the central and popular, urban and dense spots like Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, it is also about the less dense, green areas. That makes a city livable.

caption: what is the issue/conflict: After-densification in Berlin is a must, because according to the statement by the Berlin Senate, up to 2,000 new apartments should be created by 2030 according to the principle of efficiency. The more the better, of course. Getting closer together means taking no account of the valuable living conditions such as freedom, social institutions or measures to combat climate change. So in cities like Berlin, there are already only a few green areas left (and apart from the topic of climate change) this has a great impact to citizens because there is nothing to escape from the stressful everyday life. To have something, in those times of changes, that makes us feel free and safe.

caption: what is the issue/conflict: There are already modern cities, which include climate change in their long-term urban planning and provide citizens with a life-affirming togetherness and green recreation space at their homes. And also this topic belongs to the 11 UN Sustainable development goals which is: sustainable cities and communities.

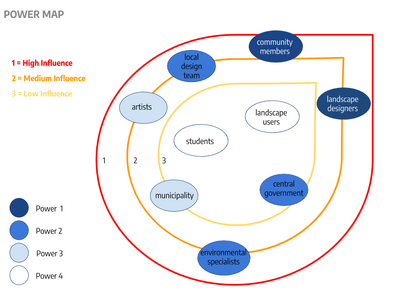

caption: who are the actors: The people affected by this topic are, of course, the citizens of berlin. But also animals suffer under the sinking number of green areas. Politicians, local government need to come to other solutions for the housing problem then just reducing those areas. So then the planners, who concretely deal with the problem, or rather the solution of the problem, can and must plan with different guidelines and regulations.

Your references:

- https://aufrichtigsein.com/mitmachen/stimme-abgeben/berlin/b%C3%A4ume-statt-beton-gr%C3%BCne-hinterh%C3%B6fe-sollen-wohnblocks-weichen/16

- https://www.partizipativ-gestalten.de/raum-fuer-kokreation-die-stadtwerkstatt-berliner-mitte/

Landscape Democracy Challenge 3: Anna Fernanda Volken

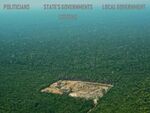

- Deforestation of Amazon Forest in Brazil

caption: why did you select this case? The Amazon rainforest has long been recognized as a repository of ecological services, not only for indigenous peoples and local communities, but also for the rest of the world. In addition, of all the world's rainforests, the Amazon is the only one that is still conserved, in terms of size and diversity. However, as forests are burned or removed and global warming intensifies, deforestation in the Amazon gradually dismantles the fragile ecological processes that have taken years to build and refine. Amazon Forest area has been reduced by 20 percent in the last 50 years due to deforestation. According to INCT-MC, the percentage of deforestation between 20% and 25% of the biome represents an inflection point - it becomes IRREVERSIBLE.

caption: what is the issue/conflict: Where once there was humid tropical rainforest and savannahs, now pastures for cattle breeding arise. The pastures are full of livestock and also termites, and the metabolic activities of these two animals also release CO2. Agricultural crops that replace forests absorb only a small fraction of the CO2 consumed by the rainforest. So, without forests, CO2 is no longer transformed by photosynthesis. Together with industrial pollution, uncontrolled deforestation in South America and elsewhere has significantly increased the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. Ministry of the Environment says there are "inconsistencies" in the Amazon Fund, the main forest protection mechanism, funded by Norway and Germany. The facility financed 103 projects - from sustainable production to inspections and records of rural properties - in the value of 650 million euros since 2008. The Bolsonaro Government's attempt to make changes in the management of the fund adds to the various initiatives that have tried to dismantle the environmental policy of the last three decades.

caption: what is the issue/conflict: President Jair Bolsonaro said in his last meeting with the American Present, Donald Trump, that he proposed opening the exploration of Amazon region in partnership with the United States. The Constitution assigns the State the duty to demarcate indigenous lands, which are areas dedicated to the sustainability of native peoples. Existing in all Brazilian states, they cover about 14% of the national surface and, except in exceptional situations, can not be exploited by non-natives. In his first day of government, President Jair Bolsonaro transferred to the Ministry of Agriculture the attribution of identifying and delimiting these territories, generating much disagreement.

caption: who are the actors? Politicians in general, focusing in this analysis in the National Government. Also state and federal deputies, who are responsible for legislate, that is, to make the laws according to what is defined in the Federal Constitution. And, of course, the population, who are responsible for voting, enforcing compliance of the laws or showing disapproval - like in this case.

Your references:

Your Democratic Change Process

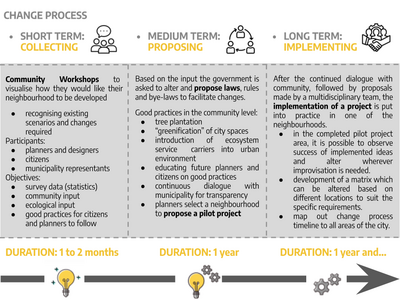

- Trees instead of concrete

Reflection

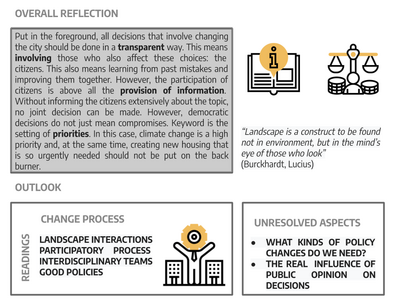

- Put in the foreground, all decisions that involve changing the city should be done in a transparent way. This means involving those who also affect these choices: the citizens. This also means learning from past mistakes and improving them together. However, the participation of citizens is above all the provision of information. Without informing the citizens extensively about the topic, no joint decision can be made. However, democratic decisions do not just mean compromises. Keyword is the setting of priorities. In this case, climate change is a high priority and, at the same time, creating new housing that is so urgently needed should not be put on the back burner.

Conclusion:

- Since landscape is an ingredient not just found in the environment, but that which takes shape of the creative acts of the humanity that also uses it, the planning process has to be inclusive of the community just like any other customary tradition.

- The creativity is filtered by elements that are influenced by our educational background, culture, and involvement. Such iterative actions bring humanity on a collaborative stand and further nourish the community while empowering the people.And that is why we should discuss how we interact with our landscape with different kinds of people, which emphasizes the designers' responsibility for social inclusion.

- As a result we get to look at a democratic landscape in the true sense that will be resilient toward the power it gives and gets back from the community that uses it and takes charge of it.

Your references

- https://aufrichtigsein.com/mitmachen/stimme-abgeben/berlin/b%C3%A4ume-statt-beton-gr%C3%BCne-hinterh%C3%B6fe-sollen-wohnblocks-weichen/16

- https://www.partizipativ-gestalten.de/raum-fuer-kokreation-die-stadtwerkstatt-berliner-mitte/

- Places in the Making:How placemaking builds places and communities : Massachusets University

- Hester, Randolph (2006): Design for Ecological Democracy - Everyday Future

- A Study into the Practice of Machizukuri

- Burckhardt, Lucius (1979): Why is landscape beautiful?